How We Learn

The Institute for Studies in Practical Spirituality, Inc.

Please be advised that this page is a work in progress. We will be adding more, and hopefully better, explanations over the next several weeks. Thanks for your patience!!

The purpose of the Institute for Studies in Practical Spirituality, Inc. is to foster the peaceful evolution and spiritual unfoldment of humankind.

The mission of the Institute for Studies in Practical Spirituality, Inc. is to provide systematic learning opportunities—in the New Thought tradition—that inspire, deepen, and strengthen both intuitive knowledge and spiritual understanding in pragmatic, demonstrable ways.

The vision of The Institute for Studies in Practical Spirituality, Inc. is to be a preeminent forum for the exchange of ideas relative to humankind’s advancement through the study of universal life principles.

Bibliography

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing—A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiples Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2006). Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons. New York: Basic Books.

Knowles, M. S. (1968). “Andragogy, Not Pedagogy.” Adult Leadership, 16(10), pp. 350–352.

Knowles. M. S. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Cambridge.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., III, Swanson, R. A., & Robinson, P. A. (2020). The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 9th ed. New York: Routledge.

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2020). Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional–guide on October 12, 2023.

Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. (2016, September 6). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides–sub–pages/blooms–taxonomy/ on October 12, 2023.

Warren, E. (2021, March 24). The 12 Ways of Learning – A New Approach to Empower Students. Retrieved from https://goodsensorylearning.com/blogs/news/different–ways–of–learning on October 12, 2023.

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, September 6). Constructivism (philosophy of education). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Constructivism_(philosophy_of_education)&oldid=1174119181 on September 18, 2023.

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, September 22). Theory of multiple intelligences. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Theory_of_multiple_intelligences&oldid=1176526026 on October 12, 2023.

Wilson, L. O. (2016). Anderson and Krathwohl Bloom’s Taxonomy Revised: Understanding the New Version of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Retrieved from https://quincycollege.edu/wp–content/uploads/Anderson–and–Krathwohl_Revised–Blooms–Taxonomy.pdf on September 17, 2023

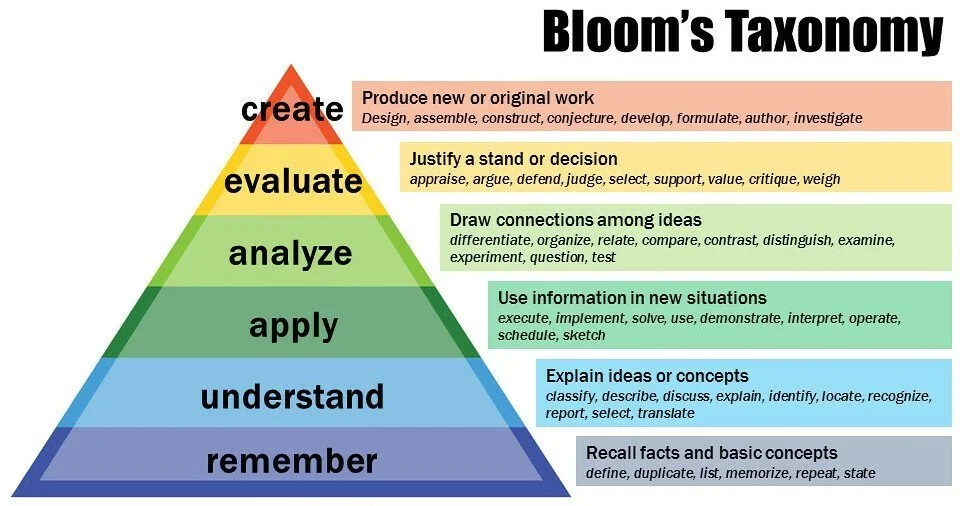

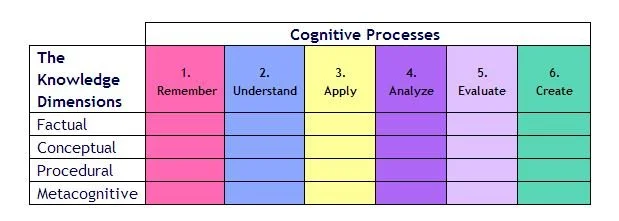

We start with the premise that learning is a lifelong endeavor. Anyone—at any age and at any time—can learn new attitudes, beliefs, and/or behaviors! We also assert when learners learn how they learn, the learning process itself is facilitated. In addition, we believe since learning is a process, it is amenable for the learner to know and understand the step-by-step factors involved in their learning. So, this is where we will start: the dimensions of knowledge as related to cognitive processes—Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; andragogy or adult learning; constructivism; multiple intelligences; and then learning “styles.”

According to Anderson, et al. (2001), there are four dimensions of knowledge: factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive. There are also six domains of knowledge: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. The relationship among the dimensions of knowledge and the domains of knowledge form a matrix and taxonomy from which learning objectives can be derived. Please click on the link below (Dr. Wilson) for a detailed explanation of how we use the theory. In the following paragraphs are brief descriptions of some of the other learning theories we employ in designing our courses of study.

Andragogy—a term coined by the German teacher Alexander Kapp (circa 1833)—was advanced in the U.S. by educator Malcolm Knowles (1968) and includes sets of assumptions and principles geared primarily toward adult learners. Central to these assumptions and principles is the notion that adults are “self–directed, experiential, problem–centered” learners and educators facilitate learning. Thus, andragogy focuses mostly on the process of learning rather than “teaching.” It supports discovery–based learning, where learners construct their own understanding through problem–solving and open collaboration.

Andragogy espouses the following principles: self–directed learning, learning by doing, relevance of the material to the learner, experience of the learner, use of all the senses, practice, personal development, and intra–/interpersonal involvement. It also makes the following assumptions: adults need to know why they need to learn something, learn experientially, approach learning as problem–solving, and learn best when the topic is of immediate value.

Constructivism—another learning theory—hypothesizes that students construct their knowledge actively. As such, “learners do not acquire knowledge and understanding by passively perceiving it within a direct process of knowledge transmission, rather they construct new understandings and knowledge through experience and social discourse, integrating new information with what they already know (prior knowledge)” (Wikipedia Contributors, September 6, 2023). A constructivist emphasizes collaboration with others for learning; ensures the active involvement of learners and promotes peer tutoring; and allows learners to foster their own learning strategy.

Constructivist ideas have been used to inform adult education. Current trends in higher education push for “active learning” based on constructivist views. Approaches based on constructivism stress the importance of mechanisms for mutual planning, diagnosis of learner needs and interests, cooperative learning climate, sequential activities for achieving the objectives, and formulation of learning objectives based on the diagnosed needs and interests. (Wikipedia Contributors, September 6, 2023)

Constructivism evolved from the work of Jean Piaget (1896–1980, Theory of Cognitive Development) and Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934, Theory of Social Constructivism). Others who contributed to constructivism include John Dewey (1859–1952) and Maria Montessori (1870–1952).

So, there is a connection between andragogy and constructivism. As with andragogy, constructivism treats instructors as “facilitators.” This places the onus for learning primarily on the learner. But this is a good thing since new learning builds upon prior knowledge and experiences of the learner. Further, both theories require an assessment of the needs and wants of the learner and collaboration between and among learners. Finally, each requires clearly identified goals and objectives for the lessons to be learned. So now we turn to a short discussion on intelligence.

Multiple intelligences is a theory that concludes individuals have a range of intelligences, rather than a single, general ability such as I.Q. Howard Gardner first proposed the theory in 1983 and suggested “a pluralistic view of the mind, recognizing many different and discrete facets of cognition, acknowledging that people have different cognitive strengths and contrasting cognitive styles” (2006, pg. 5). As it relates to the adult learner, he surmised “I do not wish to imply that . . . intelligences operate in isolation. Indeed . . . any sophisticated adult role will involve a melding of several of them [intelligences]” (2006, pg. 8). Gardner would subsequently identify nine types of intelligence: musical, bodily–kinesthetic, logical–mathematical, verbal–linguistic, visual–spatial, interpersonal, intrapersonal, naturalist, and spiritual–religious.

There are many ways or styles in which people learn—not to be confused with multiple intelligences. A common misconception, multiple intelligences are different intellectual abilities while learning styles are how learners approach a set of tasks. There are probably as many ways to learn as individuals who do the learning. But for our purposes, we have identified twelve common ways that learners engage with the learning process: visual, auditory, tactile, kinesthetic, sequential, simultaneous, verbal, interactive, logical/reflective, indirect experience, direct experience, and rhythmic/melodic.

These theories provide the backdrop (conceptual framework) for designing our learning opportunities. You will notice that we have not placed as much emphasis on the instructor as is traditional, but rather on the learner. This is because adults have knowledge and experiences that contribute to their peaceful evolution and spiritual unfoldment. Adults need only a guide or facilitator to affect their lifelong learning opportunities.

Finally, this is an abridged version of many articles and texts. It is not exhaustive and is only meant to be a guide. However, understanding the basics of how we learn will be helpful as you take this learning journey along with us!

Behavioral Psychology teaches that learning is a change of behavior through experience. While dictionary definitions posit that learning is the acquisition of knowledge and so forth, we hold to the belief that learning is indeed a change in behavior and, as such, we have designed our learning experiences to affect one's behavior or how one acts or reacts to real-world situations. So, in designing our studies, we have used a modicum of learning theories and instructional technologies from which we can appropriately affect the changes in behavior we are advocating in our day-to-day interactions.

It is very important for us to understand how we learn, and all of us are learners. As a matter of fact, it is sometimes asserted that the primary purpose for us being here is to learn, and we at The ISPS ascribe to that belief. All our courses are designed to foster the peaceful evolution and spiritual unfoldment of our learners. Each is “ecologically valid” (if we can borrow a term from research), which is to say that each study has real-world applications. Courses are designed based upon several learning theories, which are described herein.